Who gives a shit?

Introduction

Excuse my language, but who really gives a shit about shit?

Africa is growing three times faster than the global average. It is projected that by 2050, Sub Saharan Africa’s population will double to 2.5 billion by 2050 and by 2070, it will be the most populous place globally. Overpopulation has resulted in a growth of informal settlements, corruption in governance, inadequate urban planning and limited access to water resources.

‘World Toilet Day’ is celebrated on 19 November every year, to address the sanitation crises. Although toilets are a basic human right, there are still 2.3 billion people lack access to basic sanitation. The UN states that in order to fulfil SDG 6.2 ‘water and sanitation for all and end open defecation’, the world needs to work 4 times harder than it already is.

The politics of sanitation

Sanitation is often overlooked in development efforts. As George (2008:76) states ‘Sanitation was always an afterthought, if considered at all.’ In many African cultures, discussing defecation is often considered impolite and embarrassing as it is seen as a private matter. The taboo around this topic has led to it being largely ignored resulting in severe underfunding. In order to address this issue and move closer to fulfilling SDG 6.2, the stigma surrounding conversations on defecation needs be removed.

Case study: Mathare, Nairobi

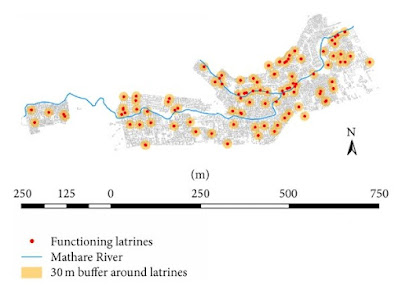

Home to 600,000 inhabitants, Mathare is one of the fastest growing urban settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Here, 85 households share one toilet, and the mean distance between a household and functioning toilet was 52 metres.

Figure 1: Map of toilets in Mathare, Nairobi

The sanitation issue: A gendered struggle

Womens' health, dignity and rights are impacted by poor urban sanitation. In Mathare, communal toilets are in the form of pit latrines (Figure 2). This a safer option compared to open defecation, but they need to be emptied and cleaned on a regular basis. Failure from the Nairobi City Council in doing so has meant that they have become privatised to be kept functional. As a result, entry now costs 5 Kenyan Shillings. Two thirds of Mathare’s population, cannot afford the cost and therefore are forced to openly defecate. Additionally, most toilets are only open from 9am-6pm. What happens if people need to use the toilet at night? By charging to use the toilet, it becomes a luxury good rather than an infrastructure that facilitates a basic need. It also turns a private bodily practice into a shared affair.

Figure 2: Pit latrines in Mathare

For women, going to the toilet is not just a public health matter, but also a matter of personal safety. Most women have to walk more than 300 metres from their homes to use the available latrines. Walking alone, especially in the dark increases risk of rape, assault and violence due to the lack of electrification. Winter (2018) found that women in Mathare who didn't have access to a nearby toilet were 40% more likely to be sexually assaulted. The lack of adequate access to toilet facilities means that many often resorted to ‘flying toilets’ (human waste disposed of in plastic bags). However, this contributed to poor health and the spread of water bourne diseases as the waste pollutes the Mathare and Gitathuru rivers. In 2018, 90% of annual deaths in Kenya were due to poor sanitation, with 65% of those deaths being girls.

Conclusion

Women are disproportionately affected by the sanitation crises. Whilst men can use alleys and open places, women are not able to do that because of wider public perceptions of decency and dignity. Communal toilets are often used, but these are poorly maintained and far from homes, making women more vulnerable to gendered violence. As a result, many women resort to open defecation, but even here many women face harassment and intimidation by members of the community, resulting in women suffering shame and indignity. So where is the win for women?

This blog was really engaging, as the message of how sanitation within the discourse of development is often overlooked, and considered as an 'afterthought' as you mention. Despite the presence of communal toilets (pit latrines), it was sad to acknowledge the gendered inequalities women face such as loss of dignity, and also the distance they must travel to go to the toilet, which puts them at risk of sexual assault. I think your map of toilets was an effective visual to use, to demonstrate this point. What do you think the solution should be, so women have fair and safe access?

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment Maya! There are several strategies that can be used to address the issue of open defecation and improve access to safe and hygienic toilets in Africa. These include:

ReplyDeleteIncreasing awareness and education: This can involve providing information about the health risks associated with open defecation and the benefits of using toilets.

Providing incentives and subsidies: Governments and organizations can provide incentives or subsidies to encourage people to use toilets and adopt more hygienic practices.

Building infrastructure: This can involve constructing toilets and sewage systems in areas where they are lacking.

Implementing community-led approaches: This can involve working with local communities to identify their needs and develop solutions that are tailored to their specific context.

Addressing the root causes of the problem: This can involve addressing issues such as poverty, lack of access to clean water, and inadequate infrastructure.

Overall, it is important to adopt a holistic approach that addresses both the immediate needs of those affected and the underlying issues that contribute to the problem of open defecation and inadequate access to toilets in Africa.